The season is finally here, which is great for most of us. But for some young up-and-coming players, it means getting cut from NHL rosters (whether now or following brief tryouts) while players who nobody would argue possess equal skill occupy the league’s fourth line spots. It’s an interesting dilemma, and one that until now nobody has to my knowledge managed to quantify. I’m only going to take the first step here, and speak in very broad generalities, but I hope that this piece will frame the debate over the use of the fourth line a little better, and present some evidence that maybe it’s time for change.

But first, a little perspective. Hockey wasn’t always about toughness or grit. In Canada, hockey’s roots lie in lacrosse, where early Canadians sought to find a winter alternative to their favored summer pastime. They implemented elements of rugby (like the no-forward pass), which certainly brought an element of ruggedness to the idea, but keeping the puck – or in the earliest days, ball – was basically as important as it’s seen to be by analytic types today. In Russia, meanwhile, hockey developed from soccer. Possession there was also critical, and simply speaking the best players played. There wasn’t much need for pests, or rats, or whatever you want to call them. It would have been out of character considering the sport’s origins.

But then the wars hit. First World War I, then World War II. Many of the top hockey players in North America, even those who had been competing in the National Hockey League, went oversees, and the league had to cope with less talent, and declining attendance. It was then that the forward pass was implemented, the blue lines were created, and in order to add some concrete excitement to a dying league, fighting was specifically outlined and legalized in the rulebook. Of course teams, fearing for their survival and suffering from a lack of talent, found guys to come in, play minimal minutes, and fight plugs on other teams. Fighting was a release for both players and fans from war tensions – to be clear, fighting had been around before, it just hadn’t been formally allowed.

Due to the lack of talent at the time, the dump and chase also became prominent. Many of the “replacement players” didn’t have the talent necessary to get by defensemen with the puck at the blueline, so coaches relied on players’ natural speed and toughness to give up the puck only to retrieve it. The practice became a staple of North American hockey, and while it was somewhat slowed by the end of the war and the return of many original players, the expansion of the 1960s allowed it to develop and thrive once again. Hockey had become watered-down, and dump-and-chase was the safest strategy for those players the coaches didn’t trust to get into the zone safely with the puck still on their stick.

Why is this important? Because there has never been an inherent necessity for toughness, at least not in the way players like Shawn Thornton, George Parros, and other enforcers embody it. Toughness is important for a player so that he doesn’t get phased by failure, so that he can stand up to bullies, so that he can fight through checks, but not in terms of the ability to fight, or to sit menacingly on the bench. The Chicago Blackhawks of the past few years have shown that, if nothing else.

So why is the fourth line necessary, in its current form, according to most hockey people? Thankfully, the dialect over the past few years from coaches has shifted from speaking about “top 6” to “top 9 forwards”, at least recognizing the importance of talent over physicality to an extent. But why should it stop there? Why shouldn’t we be talking simply about NHL and non-NHL forwards? What are the reasons why the disconnect between “top-9” and “bottom-3” forwards still exists? Is this yet another example of the NHL not adapting nearly quick enough to the evolutions in the game of hockey? Or are there still reasons to keep things as is.

I thought about it, and came up with two good reasons why I felt a conventional fourth line might be necessary:

1) Penalty Killing.

Advanced hockey analysis tends to focus on even-strength over special teams for the same reason as it focusses on shot quantity over quality: not because the latter doesn’t exist, but simply because the former is far more easily quantifiable, and thus firmer conclusions can be drawn.

Special teams are very difficult to analyze at this point because the sample sizes are small, and because units play so much time together (against very similar opposition competition) that, unlike at even-strength, it is nearly impossible to determine which individuals are responsible for success or failure.

Many fourth liners are used on the penalty kill, but whether they are truly necessary for that reason is an open question. I didn’t do any numerical analysis on this, but I would guess that – especially as the appreciation for good two-way centers has increased – the need for those specialists is on the decline. Take for example, Max Pacioretty, a player who nobody would think of as a conventional penalty killer, but who last year, thanks to his high-energy, long skating stride, active stick, constant pressure, and improved positioning, was among the best penalty-killing wingers in the game.

I would argue that even at this point, having PK specialists can help a team. Organizations can, however, fairly easily get by without them, as long as the rest of their personnel is arranged in a way to pick up the slack. This is something I might focus on in a future post.

2) Limited ice time.

The other reason that made sense to me why one wouldn’t want bottom 3 forwards treated the same way as others is because they don’t get much ice time. According to this great piece by Garret Hohl (which I will reference more later), fourth liners average 8:03 of even-strength ice time per game. If a team has a bright young player, it’s understandable why they would want them playing top minutes in the AHL, say, rather than under 10 minutes in the bigs. Development, etc. etc. The limited ice time for fourth liners, obviously, makes sense on the surface because it frees up top liners (the big guns) to play more ice time, and thus, maximize their value.

BUT.

But, here’s where opportunity cost comes into the picture. Without numerical analysis, how can you know that the conventional method actually maximizes the use of those top players, and of the team as a whole? Essentially the question is: What is the opportunity cost of demoting talented youngsters in favor of less-skilled veterans, in order to play top players top minutes, in terms of goal differential per game?

Here is my very broad and basic attempt to answer that. Obviously I recognize that the situation changes by team and by year, so further exploration would be necessary before any specific team came to a conclusion on this.

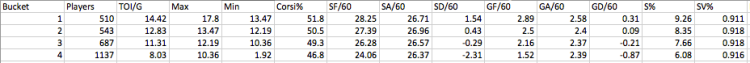

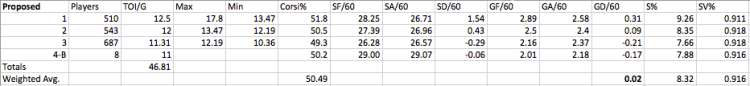

Here are the relevant columns of the first chart from that piece by Garret, which groups NHL players into buckets based on ice time. The total TOI/G at even-strength (these are all ES numbers) is 46:59, so I’m going to work under the assumption that that is approximately the amount of ES play per game. Any model for ice time needs to work within that parameter.

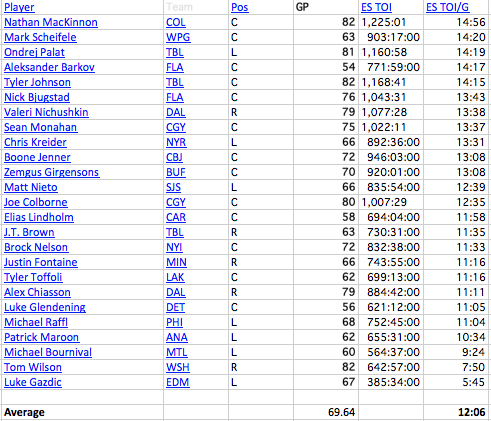

After examining this chart, I took a look at average ES ice time for rookie forwards in the NHL who played in at least 50 games last year. That number was 12:06. If you took out the three who played less than 10 minutes per game, that number would be 12:44, but the important fact I took away from that examination was that a number of teams were content with rookies averaging anywhere above about 11 minutes of ES ice time.

If somebody as talented and young as Tyler Toffoli can play 11 minutes at ES per night and a smart organization like the LA Kings can be okay with it, then the same can be said for just about anyone, I think. Presuming they’re NHL ready.

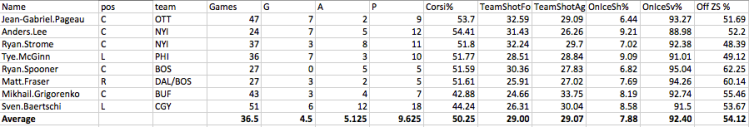

So the next thing I did was to assemble a list of young forwards who were either cut this training camp in favor of less talented NHL veterans because there was no space in the “top 9” for them, or had been in danger of it. I crowdsourced this to Twitter, and what follows is the list I decided upon.

The list of players isn’t actually very important, as long as you’re willing to accept that some young player who may miss out because they don’t fit a fourth line role could potentially have a CF% of 50.25%, as well as the rest of the production you see above.

Disclaimer: The 54.12% offensive zone starts isn’t relevant to this illustration, but I will note that that number does confound the results somewhat, so it’s something for future examination. The conventional fourth liners likely – although not necessarily – have far lower OZS%s, and therefore their CF%s are bound to be lower. I don’t think that renders this study useless, but it’s something to be taken into account.

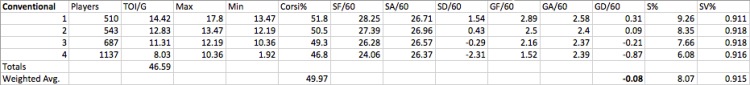

So with this list of eight rookies, I essentially made a 5th bucket, of AHL/NHL tweeners, one might say, for comparison. I took the conventional bucket format, and weighted shot and goal differentials, in unison with save and shooting percentages, to find an expected GF%. The numbers were slightly off – I’d expect from rounding with the data collection – but here’s what I found:

That bolded number is the expected goal differential per 60 minutes of even-strength ice time. What I did next was see whether there was a TOI arrangement that allowed for the following things:

1) The fourth line, now composed of young skilled players, to play at least 11 minutes

2) None of the other lines to play as little as the fourth line

3) To keep every line happy

4) To improve expected goal differential

5) Obviously, not to surpass ~47 minutes of even-strength ice time per game.

Here is what I found:

If one plays the first line 12.5 minutes (rather than 14.42), the second line plays 12 (rather than 12.83), the third line stays the same, and the fourth line plays 11 minutes, then the expected goal differential can be improved upon. The actual amounts don’t matter all that much, since the numbers are vague overall, but the point is that it could be done.

What about the fact that your top players are now only playing 12.5 minutes at even strength? Good, now they’re a) Less tired at the end of games, b) Less tired at the end of the season, c) Less injury prone. Or, taking it in another direction, they can now play more on the power play where their skill set is maximized, and even in some cases take more responsibility on the penalty kill, since the fourth line specialist is now extinct. Max Pacioretty, for example – somebody who has been injured somewhat frequently during his career, and who plays both power play and penalty kill – would certainly thrive under such an arrangement.

Conclusion.

So if you didn’t read all that, what is there to take from this piece? Essentially, based on quite rudimentary research and analysis, it appears as though the opportunity cost of cutting youngsters in favor of more established, low ice-time grinders, is very large, and ultimately isn’t worth it. Teams, by and large, would be better off playing their top-12 players overall, and more evenly distributing even-strength ice time.

You bring up good points favoring youngster over less-skilled veterans and I’m on board with that. On the other hand, your quantitative analysis leaves a lot to be desired. ZS is the crux of the matter as you correctly identified. In order to validate your study you should find rookies that share the same ZS as those veterans. Maybe you should look at young players that have split their time between the NHL and AHL for the past 2-3 years. You would probably get a better sample size.

LikeLike